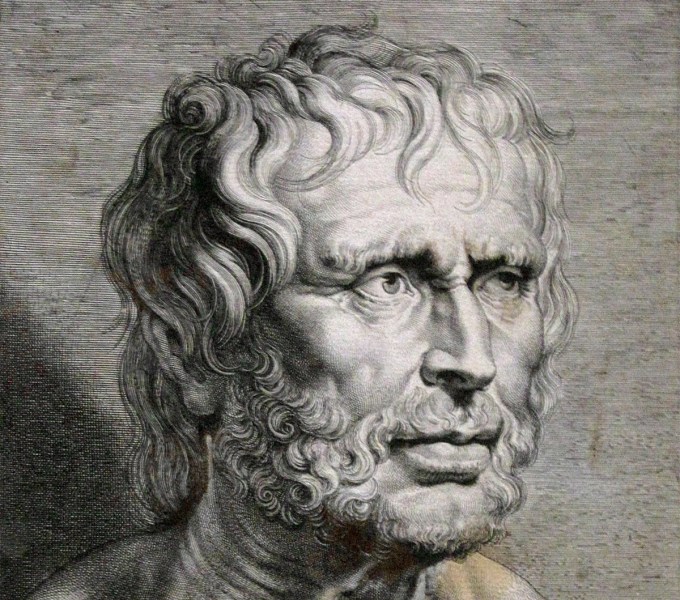

(Sketch is of Seneca the Stoic Philosopher)

The following is a chapter from an upcoming book by modern-day Stoic, Matthew D. Hutcheson titled, Friendship. We hope you enjoy it. Hutcheson’s ever increasing following consider him to be one of the world’s great living Stoics. He may also be remembered by history as one of the great practical philosophers.

Friendship

Understanding True Friendship

© 2020 Matthew D. Hutcheson

Most people on earth have heard something of the classical Greek philosophers, Socrates (470 – 399 BC), Plato (423 – 347 BC), and Aristotle (384 – 322 BC). Greek society between 510 BC and 322 BC is known as “Classical Greece.” Hence, those three are commonly referred to as “Classical Greek Philosophers.”

Classical philosophers Explored Big Picture Ideas

Socrates is known for his way of teaching. Called the Socratic method, it consists of questions presented to students in a logical sequence to help them arrive at the correct conclusion. Socrates’ contribution to Western society has been substantial. However, his contributions are not indispensable to modern life. So, we thank him kindly, but do not acrue more to him than is due.

Plato is considered to be the Western world’s “first professor.” He founded what is considered by academia to be the first university called the Academy north of Athens. Anyone who has benefitted from the structure and results of modern college can thank Plato.

Aristotle gave humanity many lasting gifts; gifts perhaps of far greater importance and direct usefulness to humanity than his two famous predecessors. Aristotle, a student at Plato’s academy, gave the world a meaningful understanding of ethics, biology, aesthetics, physics, law, and literature. Most of all, he took the intuitive system of logic developed by Socrates and developed a formal structure-of-logicical thinking academia could really upon and that is still used today.

Since this is a book about friendship, you may be asking what Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle have to do with anything.

Well, from their foundational philosophical work in the classical Greek period sprang ideas and concepts of even greater worth to human kind during the following period: the Hellenistic period.

Hellenistic Philosophers Explored Human Character and Interpersonal Relationships

After Aristotle’s death in 322 BC, the Greeks began to refer to themselves as “Hellenic.” After all, the word “Hellas” was the original word for Greece. Perhaps the Greeks used Hellas as an expression of nostalgia for its classic culture. In any event, Hellenic contributions to the world at that time took on the description of “Hellenistic.” In other words, “of, or influenced by, Greece “

During the Hellenistic period, refinements in philosophies pertaining to human character and interaction were made. In other words, instead of big picture ideas brought forth by classical philosophers, Hellenistic philosophers took a deep-dive into human nature. What makes human beings behave the way they do? Why do two people become friends? Why do some people stay friends when others cannot?

Greek philosophy, as we know it today, is predominantly Hellenistic, being developed between 322 and 30 BC.

Foremost among the Hellenistic schools of philosophical thought is that of Stoicism.

Stoicism

The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines a Stoic as a member of a school of [Hellenistic] philosophy founded by Zeno of Citium about 300 BC, holding that the wise man should be free from passion, unmoved by joy or grief, and submissive to natural law.

A “passion” in this context is an urge to act in a potentially harmful way, not to be confused with the expression of intimacy one might show to a spouse, for example.

Being “unmoved by joy or grief” does not mean an absence of joy or grief, but rather an absence of unsteadiness. Stoicism focuses on how a person deals with joy or grief, not suggesting that there should be none.

In short, the Stoic way embraces “self-control and fortitude as a means of overcoming destructive emotions.”

Stoicism is misunderstood by many to mean “emotionless living,” sort of like the Vulcans of Star Trek.

That is not a correct understanding.

While it is true the modern definition of “Stoic” is “a person who can endure pain or hardship without showing their feelings or complaining,” it is not true that the ability to endure requies an absence of sentiment.

Perhaps it is because of a Stoic’s ability to endure pain or hardship without showing their feelings or complaining that enables a Stoic to be such a good friend to another during his or her hardship. Afterall, friendship itself can be significant cause of pain or hardship in one’s life. Yet true friendship is one of life’s greatest joys.

The flip side is that Stoics loathe and refuse to put up with gossip, drama, and petty nonsense. The Cambridge Idiom Dictionary, 2nd Ed. (2006), defines “suffering fools gladly,” to mean “to become angry with people you think are stupid.” Stoics have no qualms about dropping a “friendship” cold if it becomes so infected.

It takes a lot to ruin a true friendship with a Stoic, and being stupid is one such way.

These finer points of understanding when viewed in light of friendship help us understand why true friendships flourish within the Stoic school of thought and false friendships wither away quickly.

Of the eight principal philosophers of Stoicism,Seneca, in particular, has something important to share about friendship.

(Stoicism began as a Hellenistic philosophy and was eventually adopted by the Romans. “Seneca is considered one of the foremost proponents of (Roman) Stoicism, originally an Hellenistic philosophy founded in the third century BC in Athens by Zeno of Citium.)

But First, What is True Friendship Anyway?

Two Dictionaries define a friend as follows:

Friend n. (1) A person whom one knows, likes, and trusts; (3) A person with whom one is allied in a struggle or cause; comrade.

Definition (1) identifies what I call a “soft friend”; those who are a friend when it is comfortable to be such, but sneak out the back door at the first sign of trouble. Perhaps it is safe to posit that “soft friendships” constitute most of one’s relationships.

I am not interested in “soft friendships.” In prison, such a “friend” constitutes ninety nine out of one hundred acquaintances. It is not an impossibility for an inmate to become acquainted with many thousands of other inmates, especially those with long sentences. The “99” are simply here today and gone tomorrow. Perhaps, in reality, it is like that everywhere, in or out of prison.

Notwithstanding, some of the very best friendships I have ever had were forged in prison with other inmates engaged in the same struggle as I. “I’ve got friends in low places.”

Those “1’s” are deeply loved in my life.

During my prison experience I have also formed unbreakable bonds of eternal friendship with men of high reputation and stature; I also have “friends in high places.”

I cherish them all.

It is they who are more than mere people I know, like, and trust. They are allies.

Accordingly, it is definition (3) that I find particularly interesting: “A person with whom one is allied in a struggle or cause; comrade.”

To have an ally is to have a holy connection.

An ally-friend transcends mere affection and trust, as those two sentiments are fleeting.

The Cambridge Dictionary defines ally as, “Someone who supports you, especially when other people are against you.”

Seneca says, “For what purpose, then, do I make a man my friend? In order to have someone for whom I may die, whom I may follow into exile, against whose death I may stake my own life, and pay the pledge, too.”

Seneca understood what ally-friendship means.

Do you have at least one such relationship?

“If you have nothing in life but a good friend, you’re rich,” says champion figure skater, Michelle Kwan.

Not to put words in her mouth, but I have to believe she really means, “one good ally-friend.” I think she means a Senecian friend; a friend like Seneca described.

For those still struggling to find such an ally, hopefully this book will help.

1 thought on ““Great Living Stoics””

Comments are closed.